Last month Pink Floyd frontman David Gilmour sold his guitar collection for $21.5 million, including one piece – his famed “Black Strat” Fender Stratocaster – that went for nearly $4 million to the owner of the U.S. National Football League’s Indianapolis Colts.

The “Money” singer set a musical instrument sales record in the charity auction, marking yet another milestone for a booming market just weeks after New York-based art dealer Sotheby’s Holdings (BID.N), auctioned Claude Monet’s “Meules” for $110.7 million, the most ever for an Impressionist painting.

And it is not just instruments or paintings in high demand among the world’s billionaire set. Auction houses themselves now appear to be prized vanity purchases: Just a few days before the Pink Floyd auction, Franco-Israeli cable magnate Patrick Drahi, whose firm Altice earned significant money in the United States, made a $3.7 billion bid for Sotheby’s, which had just hosted the Monet sale.

Welcome to the longest U.S. economic expansion in history, one perhaps best characterized by the excesses of extreme wealth and an ever-widening chasm between the unfathomably rich and everyone else.

Indeed, as the expansion entered its record-setting 121st month on Monday, signs of a new Gilded Age are all over.

Big-money deals are getting bigger, from corporate mergers and acquisitions, to individuals buying luxury penthouses, sports teams, yachts and all-frills pilgrimages to the ends of the earth. And while these deals grab headlines, there is a deeper trend at work. The number of billionaires in the United States has more than doubled in the last decade, from 267 in 2008 to 607 last year, according to UBS.

“The rich have gotten richer and they’ve gotten richer faster,” said John Mathews, Head of Private Wealth Management and Ultra High Net Worth at UBS (UBSG.S) Global Wealth Management. “The drive or the desire for consumption has just gone upscale.”

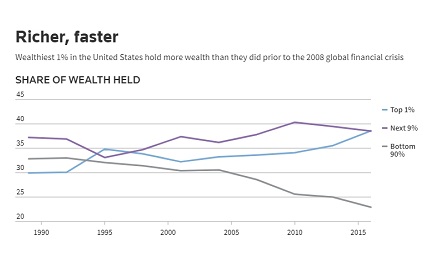

But there are also signs of struggle and stagnation at lower-income levels. The wealthiest fifth of Americans hold 88% of the country’s wealth, a share that has grown since before the crisis, Federal Reserve data through 2016 shows. Meanwhile, the number of people receiving federal food stamps tops 39 million, below the peak in 2013 but still up 40% from 2008 even though the country’s population has only grown about 8%.

Still, a decade ago, this kind of growth was not thought possible. The U.S. financial system was in a shambles and people feared bank failures could permanently undermine capitalism. Policymakers scrambled to stabilize markets and boost asset prices when U.S. housing markets unraveled. They did less to tackle income and wealth inequality.

Now, many of the signs of mega-wealth that preceded that financial crisis are once again on display.

WEALTH EFFECT

The examples are big and small.

The cost of a dinner at the French Laundry, the chic California restaurant, is up 35% to $325 per person, from $240 10 years ago, beating inflation by nearly 20%.

Undergraduate tuition at Ivy League mainstay Columbia University is a hair under $60,000 a year, up by half from $39,000 in the 2008 school year.

The U.S. stock market, measured by the S&P 500 .SPX, has tripled in the last decade.

Hedge fund boss Ken Griffin set a record for a U.S. home sale when he bought a $238 million penthouse condominium on “Billionaires’ Row” just off New York City’s Central Park.

Yet rents in New York have risen twice as fast as wages, according to StreetEasy data from 2010-2017, squeezing lower-income residents. U.S. home prices were near their lowest levels of affordability since 2008, research by ATTOM Data Solutions shows. And the number of homeless people sleeping in the city’s shelters is 70% higher than a decade ago, according to the Coalition for the Homeless, an advocacy group.

“Under-resourced areas are not getting any better; the housing opportunity for them is not getting any better,” said Carolyn Valli, CEO at Central Berkshire Habitat For Humanity, in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, at a recent economic policy event. She said high healthcare costs and a lack of large employers mean fewer jobs in some areas. Food, utilities and housing costs, meanwhile, remain high. “It doesn’t feel like a boom yet.”

Anger over what some see as the unfairness of the economy has bubbled into the country’s politics, with Democratic presidential candidates promising to lower healthcare costs, guarantee jobs and tax the rich.

Economic policymakers think the expansion could dim as stimulus from tax cuts and low interest rates fades while a U.S.-China trade skirmish brews. They worry that even the underwhelming gains made by low-income people in the last decade are fragile and that people only recently brought into the workforce could be the first fired when a recession hits.

“The benefits of this long recovery are now reaching these communities to a degree that has not been felt for many years,” Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell said last week. “Many people who in the past struggled to stay in the workforce are now getting an opportunity to add new and better chapters to their life stories. All of this underscores how important it is to sustain this expansion.”